Why Canada’s saying sorry for Hong Kong-Vancouver migrant tragedy

With Prime Minister Justin Trudeau set to apologise for Canada’s role in the tragedy that befell Sikhs aboard the Komagata Maru, which sailed for Vancouver in 1914, Stuart Heaver visits the temple in Hong Kong where the story of the voyage began

The Japanese-owned freighter Komagata Maru (background), the HMCS Rainbow and a swarm of small boats in Vancouver, in 1914. Photos: Alamy

THE JAPANESE-OWNED FREIGHTER KOMAGATA MARU (BACKGROUND), THE HMCS RAINBOW AND A SWARM OF SMALL BOATS IN VANCOUVER, IN 1914. PHOTOS: ALAMY

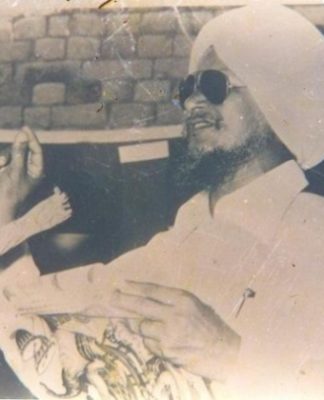

Hong Kong’s Wan Chai district may be a long way from Ottawa but, next week, when Prime Minister Justin Trudeau rises to address the Canadian parliament, Gurmel Singh will gaze up with particular pride at a large photographic print mounted on the wall of the Khalsa Diwan Sikh Temple, on Queen’s Road East.

Singh is the manager and religious instructor at the Wan Chai gurdwara (Sikh temple) and the grainy monochrome image shows a group of Sikh men dressed in turbans and formal suits, posing awkwardly on a ship’s deck in 1914. The ship is the Japanese-owned freighter Komagata Maru and, on May 18, Trudeau will issue a high-profile public apology related to the fate of those on that ship, which departed from Victoria Harbour more than a century ago, bound for Vancouver.

The Sikh community of Hong Kong has contributed tremendously to the history, development and prosperity of the city

J. IAN BURCHETT, CANADIAN CONSUL GENERAL

“Most of the 15,000-strong Hong Kong Sikh community will know about this incident because the temple is directly related to the story – it is still mentioned a lot here,” says Singh.

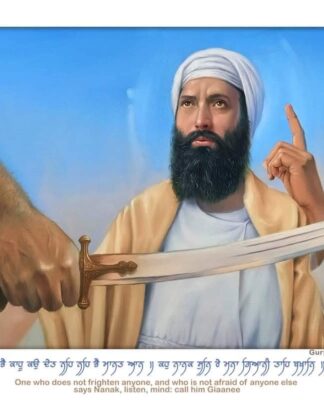

Hundreds of Sikh passengers and their self-appointed leader, Baba Gurdit Singh, prayed at the temple before boarding the specially chartered ship. It is Gurdit Singh and his seven-year-old son, Balwant, who are staring uncertainly at the camera in the photograph ahead of a voyage that was to end in bloodshed.

A photo of the Sikhs who sailed to Canada hangs in Hong Kong’s Khalsa Diwan Sikh Temple. Photo: Felix Wong

GURDIT SINGH WAS A 55-YEAR-OLD, self-made merchant, originally from the Punjab region, in northeast India, who was living and working in Malaya but had come to Hong Kong in 1914 to pursue a legal case against a business rival. He came from a modest background and had received little in the way of formal education, but he was sharp, well-connected, articulate – and litigious. While visiting the Khalsa Diwan temple he discovered that many fellow Sikhs, most in transit from India, were attempting to emigrate to Canada, and he decided to help them.

There was a considerable Sikh community in Hong Kong and the gurdwara had been built, primarily by Sikh soldiers serving in the British Army, in 1901.

Past wrongs admitted but others seek justice

“Sikhs have a reputation for being honest, loyal and fearless – we are very peaceful but we know when it’s time to fight,” says Gurmel Singh. Those characteristics were recognised by the British authorities.

Within the British Indian Army, the Sikh regiments enjoyed an unrivalled reputation for bravery and loyalty. They were central to Britain’s military ambitions in China and Southeast Asia and more than 80,000 were to lose their lives fighting for the empire in the two world wars.

Canadian forces assemble on a Vancouver pier during the Komagata Maru incident.

An embryonic Hong Kong police force, a night guard formed by Captain J. Bruce in 1844, consisted mostly of Sikhs drafted from British Indian regiments stationed locally, and, from 1862, Sikhs were recruited directly from Punjab. They were the only officers permitted to wear turbans instead of uniform hats or helmets and were considered so essential to law enforcement, senior British officers were dispatched to Punjab to learn their language.

“The Sikh community of Hong Kong has contributed tremendously to the history, development and prosperity of the city,” says J. Ian Burchett, Canadian consul general to Hong Kong, who believes the formal apology on May 18 is both relevant and significant. “Canada is an inclusive country and continues to demonstrate that our diversity is one of [the nation’s] biggest strengths.”

From 1867 to 1967, Canada had a white-only immigration policy … the notion of ‘white Canada’ was repeated over and over again

PROFESSOR ALI KAZIMI

In 1914, however, official attitudes were considerably less enlightened.

While it is a fundamental principle of the Sikh religion that there is one god common to all faiths and that all people are equal, this was not a mantra widely repeated within the British empire. Despite all passengers on the Komagata Maru being British subjects and many of their party being highly decorated former soldiers in the British Army, immigration of any South Asian to Canada (which would not achieve full independence from Britain until 1931) was a contentious issue.

The ship’s passengers wait for news.

A South China Morning Post report dated March 31, 1914.

There was a hysterical fear of a “brown invasion” and a white-only immigration policy had been covertly implemented in Canada in 1909. The legislation decreed that anyone seeking residence in Canada must arrive by continuous passage from their native country and must be in possession of a large amount of cash. It was subsequently engineered in such a way that there were no continuous sailings from Indian ports to Canada, so even though the passengers on the Komagata Maru had the necessary funds, there was no way they could meet all the requirements for entry.

“From 1867 to 1967, Canada had a white-only immigration policy … the notion of ‘white Canada’ was repeated over and over again,” says Canadian-Indian filmmaker Professor Ali Kazimi, who made an award-winning documentary about the Komagata Maru incident in 2004. Sikhs were encouraged to fight and die to protect the British empire but could not travel freely within it, even if still proudly wearing their service khaki and medals.

The acute sensitivity about Gurdit Singh’s planned voyage was also heightened by the rumblings of militant Indian nationalism and the Ghadar Party, which was formed in North America in 1913 by Punjabi Indians seeking independence for India from British rule. With the first world war in the offing and the empire dependent on Sikhs for its internal security, the authorities could not afford any incidents that might stir Indian patriotism.

Gurdit Singh (front left) with his son aboard the ship.

When Singh managed to charter the Komagata Maru for HK$11,000 per month, he had no problem selling berths – until he was arrested by the Hong Kong police, for selling tickets for an illegal journey. Many loyal Sikhs got cold feet when they realised the voyage was not endorsed by the authorities so Singh was obliged to send assistants to Shanghai, to try and drum up business there.

Opinion remains divided on whether Singh was a philanthropic businessman trying to help fellow Sikhs, an entrepreneur seeking to exploit a commercial opportunity or a radical looking to challenge the status quo. He was probably a combination of all three and had been encouraged by an incident the previous November, when 38 Sikh passengers had been unexpectedly admitted into Canada after having arrived on another steamship, the Panama Maru, following a legal challenge in the Canadian courts.

‘We’re back’: New Canadian PM Justin Trudeau promises to restore his country’s reputation as compassionate and constructive

When Hong Kong governor Francis May received no reply from the Canadian authorities to his inquiry as to whether the Komagata Maru would be permitted to dock in Vancouver and was soothed by assurances from Singh that there was no political motivation behind his voyage, the Sikh was released from custody. His ship set sail on April 4, bound for Vancouver, with just over 150 passengers, including Singh, who was determined to lead the voyage to its conclusion.

By the time the ship reached Burrard Inlet, near Vancouver, on May 23, there were 376 Punjabis, including two women, on board, more having joined in Shanghai and Japan, and the Canadian press were already in a heightened state of xenophobic frenzy.

Sikh men meet with a Canadian immigration official during the standoff.

“Hindu invaders now in the city harbour on Komagata Maru,” screamed a front-page headline in the Vancouver Sun and a pugnacious local member of parliament, H.H. Stevens, and immigration official Malcolm Reid made every effort to resist the “invasion”.

The ship was not allowed to dock and everyone including Singh, the named charterer and a recognised merchant, was forbidden from stepping ashore, even to visit the bank to pay the overdue charter instalment. Singh was not even applying for immigration but the formalities were deliberately dragged out in the hope that, if he could be prevented from paying for the charter, the ship would be recalled to Hong Kong.

Conditions on board worsened as week after week passed. The Komagata Maru was a freighter, not a passenger liner, and the facilities for the passengers, sleeping on crude wooden benches, were very basic. Fresh water and provisions were withheld and tempers were strained to the limit as a shore committee of resident Indians was formed. The lawyer who had achieved success in the Panama Maru case, J. Edward Bird, was engaged to fight their case.

“We are British citizens and we consider we have a right to visit any part of the empire. We are determined to make this a test case and if we are refused entrance into your country, the matter will not end here,” Singh told the intransigent immigration officials, according to a detailed account of the stand-off: The Voyage of the Komagata Maru, by Hugh Johnston.

Journalists and immigration official Malcolm Reid (centre) and, to his left, politician H.H. Stevens aboard the Komagata Maru.

Singh was in a defiant mood but he was unaware that the Canadian government had closed the legal loopholes Bird had been able to exploit the previous year.

Reid’s plan to prevent Singh from paying the charter fee backfired when the Indian shore committee raised the money themselves and became the proxy charterers of the Komagata Maru. They further promised a bond for the passengers, making headlines in the Hong Kong press.

An error-filled SCMP report published on June 23, 1914.

“Hindus in Vancouver have offered $1,000,000 in cash and property as bail for their countrymen on the Komagata Maru if they are allowed to land pending the decision of the courts,” reported the South China Morning Post on June 5, 1914, but Reid was having none of it. No one was allowed ashore except under escort for immigration interviews, and armed guards in a patrol launch circled the vessel night and day.

“Gurdit Singh is even more a prisoner than if he were in a penitentiary,” Bird complained, as the days dragged on with no solution in sight.

On June 24, the passengers sent a telegraph to the governor general.

“Many requests to (you) for water but useless better order shoot than this miserable death,” they complained, and it was remarkable how order was maintained on board as the frustration, thirst, hunger and filth increased.

“Reid had shown himself indifferent to the welfare of the passengers and with no good reason because the government gave away nothing by ordering supplies for them,” writes Johnston.

Other SCMP reports from 1914.

After protracted legal wrangling, the test case fought by Bird was defeated in the Court of Appeal on July 3, but the Indian shore committee, now the charterers, refused to authorise the departure of the Komagata Maru. As delays continued, an armed boarding party of Canadian immigration officials was repelled by the defiant Sikhs, hurling lumps of coal. The warship HMCS Rainbow was then ordered to Vancouver and arrived on July 21, escorted by a small flotilla of yachts and pleasure vessels. Marines prepared to storm the Komagata Maru with bayonets fixed, to arrest the ringleaders and force the captain to weigh anchor and leave.

That evening, unarmed and defiant Sikhs could be heard on the quarterdeck of their ship, singing hymns and patriotic war songs and vowing to fight to the death. Vancouver closed for business as the shore was lined with members of the public in carnival mood, eager to witness a potentially violent climax to the protracted dispute.

Violence was averted by a last-minute deal secured by the shore committee. The Komagata Maru’s Japanese captain weighed anchor just after 5am on July 23 and left Vancouver with all but the handful of passengers who had been able to prove previous Canadian residency.

Those men, women and four children, having been on board without relief for just over 100 days and having endured injustice, abuse, threats, hunger and thirst were now heading back to where they started: Hong Kong.

“[Canada] needs to acknowledge that our history includes darker moments. As a nation, we should never forget the prejudice suffered by the Sikh community at the hands of the Canadian government of the day. We should not – and we will not. An apology made in the House of Commons will not erase the pain and suffering of those who lived through that shameful experience. But an apology is not only the appropriate action to take, it’s the right action to take,” said Trudeau, in a statement provided to Post Magazine by the Canadian consul general.

“It is a very appreciated apology because it is a good lesson for the whole world: that even after a long time has passed, we can still support equality and justice,” says Gurmel Singh, but the story of the Komagata Maru and its Sikh passengers did not end once they left Canadian waters. They were headed for an even more tragic episode that no one has ever apologised for.

A 2014 Canadian postage stamp commemorates the incident.

No sooner had the ship left Vancouver than the Hong Kong authorities were making every effort to ensure it did not return here.

“It is certain that there will be no employment for a large majority of the men here,” wrote May to the Canadian government and, when the ship arrived in Yokohama, Japan, on August 16, its passengers received a written threat from the colonial secretary that he would arrest them for vagrancy if they landed in Hong Kong.

The first world war was now in progress and the Sikhs were persona non grata in a city many had helped build. A deal was struck to divert the ship to Calcutta. The Komagata Maru, which set sail, full of hope, for Vancouver on April 4 arrived 27km downstream from Calcutta, in the railway port of Budge Budge, on September 29, 1914.

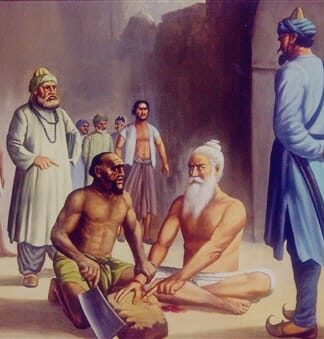

There are many conflicting accounts of exactly what happened next but Indian officials told Gurdit Singh that all passengers were required to take a special train to Punjab, and return to their villages. This did not suit Singh, who needed to go to the city of Calcutta to complete the shipping formalities. He also wished to petition the governor and to deposit the Guru Granth Sahib (the Sikh holy book) in the gurdwara in the city. Being the charismatic man that he was, Singh was followed by most of his fellow travellers, but their path to the city was blocked by the police and they were pressed back towards the docks. A scuffle broke out, shots were fired and the British Army opened fire with .303 rifles. There was bloodshed and chaos and 20 passengers lost their lives. Many more were arrested and imprisoned, or forcibly confined to their home villages for the duration of the war.

The Komagata Maru monument in Vancouver.

Singh escaped with his son and lived in hiding until 1922, eventually surrendering to the authorities, after a meeting with Mahatma Gandhi. He was imprisoned for five years but always maintained there was no political motivation to the Komagata Maru voyage. In 1952, while suffering from poor health, he persuaded Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru to install a large memorial, which still stands, at Budge Budge, to commemorate the massacre. Singh died two years later, in his mid-90s.

Full citizenship in Canada was only granted to Indian nationals after Indian independence was achieved in 1947. Many Sikhs think their basic human rights are still being denied in India, there are reports of them being randomly attacked in the United States in the mistaken belief they are Muslims and Gurmel Singh says that while they enjoy legal equality in Hong Kong, there is nevertheless some “hidden discrimination” based on public misunderstanding of Sikh culture and their contribution to the city.

“I feel very proud about this event – they represented Hong Kong and India and they only wanted a better life in Canada,” says Singh’s assistant, Manjinder Singh, who studied history at university in Amritsar, in Punjab state.

“They wanted to effect a change in the law,” he says, and like his colleague, he welcomes the apology from Trudeau and thinks it represents “a lesson for the wider world” – and a timely one at that.

Source: With thanks from South China Morning post